Maxwell'scher Dämon

Aus Daimon

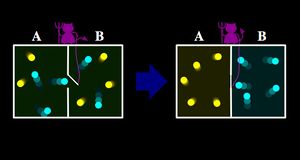

Der schottische Physiker James Clerk Maxwell (1831 – 1879) veröffentlichte in Theorie der Wärme (1871) ein Gedankenexperiment, mit dem er den Zweiten Hauptsatz der Thermodynamik hinterfragte. Das Gedankenexperiment beschreibt einen Behälter, der von einer Klappe in zwei Kammern getrennt wird. Beide Hälften enthalten zunächst ein Gas von gleicher Temperatur. Ein fiktives Wesen, das 1874 von William Thomson alias Lord Kelvin als Dämon bezeichnet wurde, ist nach Maxwell mit Fähigkeiten ausgestattet, die „so geschärft sind, dass es jedes Molecül bei dessen Bewegung verfolgen kann“. Der Dämon misst Position und Geschwindigkeit der Teilchen und fungiert als Türwächter. Er wird seiner Etymolgie des Zu- und Verteilers gerecht, indem er die Klappe öffnet und schließt, um die schnellen bzw. heißen Moleküle der einen und die langsamen bzw. kalten Moleküle der anderen Hälfte des Behälters zuzuteilen. Maxwell geht bei diesem Experiment von der idealen Bedingung aus, bei der weder die Messung noch das Öffnen und Schließen der Klappe Energie verbraucht. Der Dämon schafft Ordnung in Form einer Temperaturdifferenz, durch die eine Wärmekraftmaschine betrieben werden könnte. Damit wäre ein Perpetuum mobile gefunden und der Zweite Hauptsatz der Thermodynamik verletzt. In Theory of Heat (1871) schreibt J.C. Maxwell: „One of the best established facts in thermodynamics is that it is impossible in a system enclosed in an envelope which permits neither change of volume nor passage of heat, and in which both the temperature and the pressure are everywhere the same, to produce any inequality of temperature or pressure without the expenditure of work. This is the second law of thermodynamics, and it is undoubtedly true as long as we can deal with bodies only in mass, and have no power of perceiving or handling the separate molecules of which they are made up. But if we conceive a being whose faculties are so sharpened that he can follow every molecule in its course, such a being, whose attributes are still as essentially finite as your own, would be able to do what is at present impossible to us. For we have seen that the molecules in a vessel full of air at uniform termperature are moving with velocities by no means uniform, though the mean velocity of any great number of them, arbitrarily selected, is almost exactly uniform. Now let us suppose that such a vessel is divided into two portions, A and B, by a division in which there is a small hole, and that a being, who can see the individual molecules, opens and closes this hole, so as to allow only the swifter molecules to pass from A to B, and only the slower ones to pass from B to A. He will thus, without expenditure of work, raise the temperature of B and lower that of A, in contradiction to the second law of thermodynamics."[1]

Obgleich Maxwell von einem Modell ausging, bei dem innerhalb eines Systems alle Variablen bekannt sind und Messung, Übertragung und Datenauswertung ein einheitliches Feld bilden, wird das Dilemma, das aus diesem Gedankenexperiment resultiert, bis in die Gegenwart von Physikern diskutiert.[2] Maxwell folgte dem Monismus der mechanistischen Epistemologie und glaubte an einen Dämon, der mit zunehmender Genauigkeit einen Blick auf die Totalität der Wirklichkeit zulässt. Unschärfe- und Beobachterrelation scheinen dieser Totalität im Sinne des Laplace'schen Dämons eine Ende bereitet zu haben.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ J.C. Maxwell, Theory of Heat, London 1875, S. 328-329.

- ↑ Vgl. A molecular information ratchet

Weblinks

Maxwell's Demon: Nano Machine Of The Future Captures Great Scientist's Bold Vision

Charles H. Bennett: Notes on Landauer’s principle, reversible computation, and Maxwell’s Demon

Jeffrey Bub: Maxwell's demon and the thermodynamics of computation