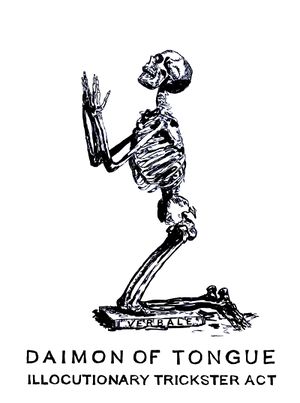

VERBALY

Aus Daimon

VERBALY: DAEMON OF TONGUE

Nothing new under the brilliant sun of the identical. Logical redundancies, mechanical equilibriums, genetic invariants, material stabilities. How happy we were when our problems had not yet been solved. The glass façades gleam in the warm evening light, making the sun set in the east. Seen from the thirtieth floor, the luxury cars glitter like the chitin shells of little dung beetles creeping across the shimmering asphalt in a sea of hot exhaust fumes. Time to leave, time to turn on the language machine. Just another sip of Glenmorangie for a nimble tongue, and off we go to enter the fray. Past Maxwell, the bouncer guarding the social beyond, another fourteen floors up toward the sky, and a soft murmur mingles with “Demons Are Forever.” Quantum eroticism is in the air, stimulating the distinct chaos of human particles in space. It is one of those evenings when minute differences in the initial conditions result in divergent modes of behavior. Words leap back and forth between people, quanta of sorts that destabilize the social determinacy of neuronal processes. Like radium nuclei, sentences decay into flimsy specks of meaning, coalescing into undefined events. Language becomes detached from its speakers; the room teems with semantic viruses. Lingonella, the pathogen causing langage diarrhea, travels on fine spherical droplets through intestinal pathways before entering the brain and infesting the Broca’s area. Colloquially known as verbaly, the most distinctive symptom in which the illness manifests itself is the irresistible urge to unleash a barrage of words at any opportunity. In the middle of a harmless conversation, the demon butts in, messing with speech and taking command of the columns of words. Fast-talkers and nifty acrobats of the tongue are especially prone to the ailment, which caused several scandals when it first emerged. People have become used to the cyclical epidemics, but what is so insidious about it is the dissociation of the person, the nagging question even the healthy ask themselves: who or what is it that is speaking here? Encouraged by unexpected early successes, a few neo-expressive subversive littérateurs tried to draw ongoing profit from their illness by cultivating a chronic verbaly that ruined their health, their bodies bloated beyond recognition.

Historically, scholars conjectured early on that language, even though it is internal to man, has an independent, extrinsic existence that exerts violence against man himself. Man does not just speak, he is also spoken by language, or as a master thinker wrote—and did not say—man is only ostensibly the language machine’s master. In reality, the machine puts language into operation and controls the essence of man. Philosophers knew about the existence of lingonellae long before physicians and biotechnologists discovered them. Catholics called the pathogen Holy Spirit, earlier on, it was known as the “Sacred Disease,” and Socrates’ name for it was daimonion. An ancient plague; the entropic metaphysician Philipp Mainländer called it the mind’s pestilence. The penthouse keeps filling up with overseas art collectors, silicone-padded starlets, it girls, and hip artists. Chinese investors stack their plates high with lobster tails, roast beef, and cream cakes and then, with rapid rustic gestures, stuff their faces. German critics are in a good mood, chewing on fist-sized filet steaks and drinking Californian Cabernet Sauvignon. A group of Italians and Frenchmen is enjoying a bottle of Brunello, their gazes languidly fixed on the life-size golden horses galloping into the night sky on the parapet of the terrace. When the band intones a punk song, the fever rises and the verbal mood seizes the musicians’ bodies. They talk with all their members, shaking and spitting their names, mixed with blood, on the stage. The song burns through people’s guts like a semantic worm, and an irresistible force sucks them into the deep hole of an inevitable nothingness that feeds the emptiness of existence. No contingency of words can redeem, no metaphysical opium drown out, the neuronal coprophilia, no confabulation machine is strong enough to escape the confusion. The spirit is not obsessed, it is the product of an obsession that thirsts for the energies of grand geniuses, a belles-lettres curse whose reading renders the horror finite. Humans owe the insight to verbaly that they are besides language, besides their sensations and needs. They grasp that they are virtual pawns, loitering in holding patterns and awaiting the endless penetrations of the demon. Verbaly is a fate one makes one’s peace with or perishes. What remained unsaid sowed disunion between people; what is said now kills them and unites them in the yearning for the last things left for which there are no words.

More and more people stream into the rooms. On the terrace, young bodies crawl on the floor, engaged in tellurian games and stretching their buttocks toward the sky so that they reflect the moonlight. At the bar, lifeless figures sputter words until they stiffen in loneliness. A few intellectuals try to twist the words and speak in tropes. The circulation of syllables contorts their bodies into enigmatic hieroglyphics. They believe in the meaning of language and its hidden topological order. They suffer from metalepsis, and from their verbal displacements grow rhetorical cascades, metonymies, catachreses, synecdoches, and antonomasias. A chic art audience looks on, recognizable by the streaks of menstrual blood across their shoes. Confident of their style and rich, they feel they are an elite. They hate global corporations and brands, at least the cheap ones that cater to the masses, pretending to be critical, left-wing, discursive, enlightened. They wear clothes by Prada, confusing life with lifestyle, art with accessories. Joined by a horde of neophytes, they listen to the words of Perdurabo, an artist who lacks an ordinary metabolism: he has a metadiabolism instead. He invokes the peaches of eternal life and the doors of the world that open behind the veil of matter. He is in constant transformation, has hundreds of names, is called Count Vladimir Svareff, Lord Middlesex, Prince Chioa Khan, Baphomet, Paramahansa. He brushes all taboos aside and accepts no social axiom. He detests living in his own skin, which is too large for his size and dotted with beauty spots all over. His devotees call him Hash Daddy, his lovers describe him as a Sisyphus of animal desires. He is a scatologist through and through, and his pictures are paradise machines of dirty fantasies.

Only a few minimalist artists remain taciturn. They convey that they do not want to convey any message, they say that there is nothing to say, they incessantly signify that there is no signification. They are modern fundamentalists of form, worshipping at the altar of stop making sense and dividing the world in dualist fashion by casting their lot with mythical anti-narration and crawling away into the hole of immanence. They are ventriloquists and think with their bowels. They are flesh and medium for the long worm of endless repetition that has been cloning the world since time immemorial.

You take things firmly in hand, and suddenly they twist like a drilling pounder and put your shoulder out of joint. Things resist and start to revolt. That is the insurrection of language in things. From now on it is a certainty: language hides in every single detail, in every groove, controlling the world. Humans must submit to its dictatorial command. Any attempt to explain what has been said or reconcile it to actions enmeshes in endless stories. The language machine is a confabulation machine that leads deeper and deeper into the beyond of meaning. The gaps between the words are stopped with words until, in their forever unceasing undulations, they bring meaning to a halt. The words do not obey the old economy of langage, they form a flow of ectoplasmic saliva that shapes things the way a wild river does. They infect matter, their semes fuse with quarks and build polymer chains with each sentence. That is the misery and the feast of the signifiers, the bursting of the dam between language and things. Verbaly engenders its own reality, whose living elements conjure the unforeseen. It is the autonomous state of language, full of references to the outside world but devoid of any to the world within. The search for how things are connected comes to an end. The web of words and things melts down to a single point of systemic existence. Poetry lived off the annihilation of language by language, the dearth of words that made it possible to say things. Verbaly avenges language. It drowns man in his quest for meaning.

- Thomas Feuerstein, VERBALE (deutsch)

- Video: VERBALE, Video, 10 min., 2007. Video und Text: Thomas Feuerstein, Stimme: Dirk Stermann

- Vinyl: DAIMON NLP

- Ausstellung: Verbale: Daimon of Tongue